Published on: 10/06/2025

This news was posted by Oregon Today News

Description

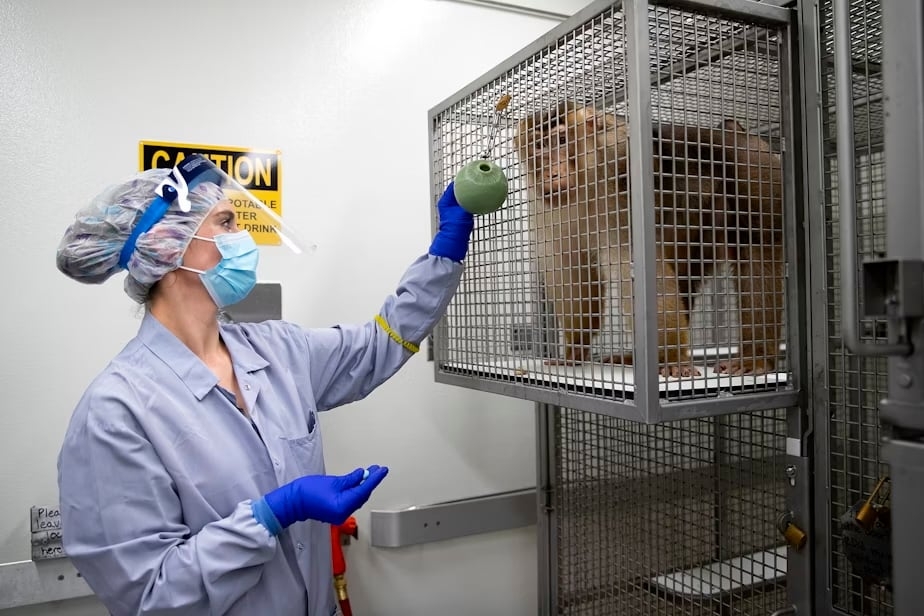

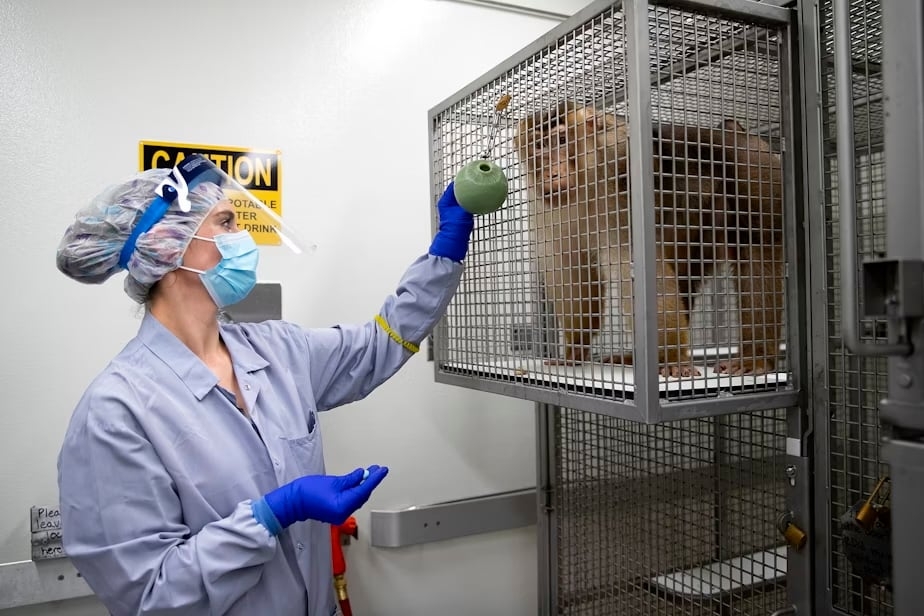

The mice cages tend to be quiet. On a recent walk through the animal labs at the University of Washington in Seattle, the ferrets were listening to ocean and bird sounds.

But the monkeys at the Washington National Primate Center were listening to Bobby Brown’s “Roni.”

“Classical music and talk radio, they seem to really like,” said Dr. Melissa Berg, a veterinarian walking between cages. “They seem to really like Disney movies and Animal Planet and anything that has other animals that they can watch.”

Berg and the staff try lots of activities to enrich the lives of these caged pigtailed macaques: freezing their food into astro-turf so they can sort of forage, making them climb up the side of the cage for peanuts.

But the monkeys find their own enrichment. A few feet away from Dr. Berg, a 35-pound male named Thor — handsome but arthritic — suddenly figured out how to unlatch and grab a piece of plastic out of the food hopper on his cage.

“You need to not do that, sir,” said Nelly Nicklason, the husbandry manager. “This is why my job is fun, because it’s constantly trying to be smarter than the monkeys, and every single day being reminded that you are not smarter than the monkeys.”

Last year, there were nearly 1,000 monkeys supporting UW research, according to UW’s animal census, as well as 436 frogs, 136 pigs, 175 rabbits, gerbils and hamsters, 178 ferrets, 4,000 rats, 161,000 mice, 5,000 birds, 3,000 cephalopods, 20 cows, 20 dogs, and over 200,000 fish.

These monkeys and their predecessors, the center boasts, have shed light on Covid transmission and helped develop life-changing technologies such as brain-computer interfaces and the first generation of cochlear implants. Important drugs like the HIV prevention medicine known as PrEP were tested on monkeys at this center before they went to human trials.

“Non-human primates are used for research only when there’s no other model that will work,” said Deborah Fuller, the center’s director. “When we write a grant, we have to say, ‘Why can’t you use something else?’ We have to justify it.”

But the intelligence and personality of monkeys like Thor, who does a duck-face “len” to newcomers to show he’s friendly, has been a driving argument from the animal-rights movement to end experiments and stop caging them.

It’s a movement that has been more associated with the political left, but during his second term, President Trump has closed an animal lab in West Virginia and canceled nearly $28 million in animal lab funding in his second term.

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. has announced there will be a “dramatic reduction in animal testing” at the Food and Drug Administration.

Animal-rights groups like PETA, which has called on Trump to claw back funding from this UW facility, smell victory.

“It’s so close,” said Dr. Lisa Jones-Engel, who worked as a primate scientist at the National Primate Center for 14 years. “I wake up every day just waiting to see what the news says and and just — just waiting for that announcement.”

Humanity of non-human primates

Dr. Lisa Jones-Engel studied these pigtail macaques in the wild. Over a decade ago, she was in Bangladesh trapping them for samples when she accidentally caught an infant along with a mother.

After the monkeys woke up from anesthesia, Jones-Engel went to release them.

“I tilt this giant cage back. Boom. The monkeys take off,” Jones-Engel said. “I heard the squeak, and I looked down, and that infant was clinging on to the netting of the cage. And I thought, ‘Oh, no.’”

The mother heard the squeak too, turned around, and risked captivity again to get her baby.

“She did exactly what I would do if my child was in that situation,” Jones-Engel said. After that, going back to the lab in Seattle, Jones-Engel couldn’t convince herself caging monkeys wasn’t having an effect on their wellbeing.

“The sounds that you hear in the lab — those are generally not good sounds,” Jones-Engel said. “You hear the infants who have been pulled from the moms, who are just making the sound that says, ‘I am terrified. I’m afraid. Where is my mother?’ You hear the moms vocalizing, ‘Where is my child?’ You hear the males just angry.”

Jones-Engel left the center in 2016, and in 2019 stopped teaching at UW and joined PETA, which has made a mission of closing all seven primate research centers in the U.S.

Jones-Engel feels closer to that goal more than ever, and not just because of the political shift. A few weeks ago, through a public records request, she received a National Scientific Advisory Board report from 2024 that said faculty feel university leadership no longer support the center, there is “organizational dysfunction bordering on chaos,” and 50% turnover of lower-level husbandry staff each year.

That report was created during a tumult of bad headlines for the Primate Research Center: a federal inspection found the center at fault after a rhesus macaque died during a cranial implant, shipments were halted from its Arizona breeding facility for six months after monkeys arrived in poor health, and the center’s director was dismissed.

But the advisory board report also said the center is “fulfilling its dual promises of high scientific achievement and world leading standards of animal care.” Fuller, who stepped in last year as director, said the center is “very well supported” by university administration, and procedures going awry are rare when the center is doing “10,000 a month.”

“Unexpected things happen, even when we try to predict them. That’s the nature of biomedical research,” Fuller said. Animal rights activists, she said, “don’t give a crap about the cures or what we’re working on. All they want to do is shut us down. So any minor little thing that happens, any adverse event that happens, they’re going to escalate that.”

Is animal testing the only way, forever?

For staff veterinarians such as Berg, caring for and loving monkeys like Thor is both heartbreaking — because while some monkeys can be adopted out or re-homed in reserves, most are euthanized and necropsied for tissue — and transcendent. Berg went into veterinary medicine after her mother was saved from cancer by chemotherapy that was tested on macaques.

“There are days when we lose animals that we love… and we mourn and we grieve, and we do what we need to do to show up for the other monkeys that still need us. But on those days, I can lean on my mom and tell her what happened, and she says, ‘But they’re doing the job that they need to do so that they can save people like me,’” Berg said.

Offices in the center are adorned with the handprints of macaques who have passed on.

“Every single animal here is making the ultimate sacrifice for other animals and for people every single day, and so I will spend the rest of my life showing up for them, because there was some monkey somewhere, that I’ll never have the opportunity to know, that is the reason that my mom is still here,” Berg said.

Critics argue that with 21st-century science, animal testing can become a thing of the past. Whereas animal trials are usually completed before human trials, during the pandemic Moderna and Pfizer’s COVID vaccines were tested on humans and animals at the same time. Computer models, 3D-printed tissues and even artificial intelligence drawing on all published studies might one day replace the need for animal testing.

The National Institutes of Health under Trump has started moving in this direction, announcing its intention to fund and research other models and set up a center for standardizing lab-grown organs. The NIH’s acting deputy director for strategic initiatives said she hopes that in five years, animal testing will be the alternative to these new models rather than the default.

“I give the Trump administration and NIH a lot of credit in starting down that road,” Paul Locke, who studies the transition to non-animal methods at Johns Hopkins’ school of public health, told KUOW.

But Locke said those replacements are not ready to “pull off the shelf and use.”

“If we ended all animal testing now, in my estimation, it would not be good for science. It would not be good for human health,” Locke said. He said that even as an optimist, it may be 50 years before animal testing could end entirely.

Dr. Jones-Engel of PETA disagreed, pointing to studies that say how animals react to things like exposure can be poor predictors of how humans react.

“The real danger isn’t moving on too quickly, it’s clinging to a model that has already failed us,” Jones-Engel said via email. “Science doesn’t need another 50 years of excuses—it needs the courage to follow the evidence and let animal testing go.”

News Source : https://www.opb.org/article/2025/10/06/trump-might-shut-down-uw-primate-research-center-should-he/

Other Related News

10/06/2025

Prosecutors charged Sanchez with one felony and three misdemeanors for his alleged role in...

10/06/2025

The chains new limited-time offering features bite-sized hand-cut steak pieces seasoned wi...

10/06/2025

Semiconductor designer AMD will supply its chips to artificial intelligence company OpenAI...

10/06/2025

CHICAGO Illinois Gov JB Pritzker is scheduled to hold a news conference Monday afternoon ...

10/06/2025