Published on: 12/12/2025

This news was posted by Oregon Today News

Description

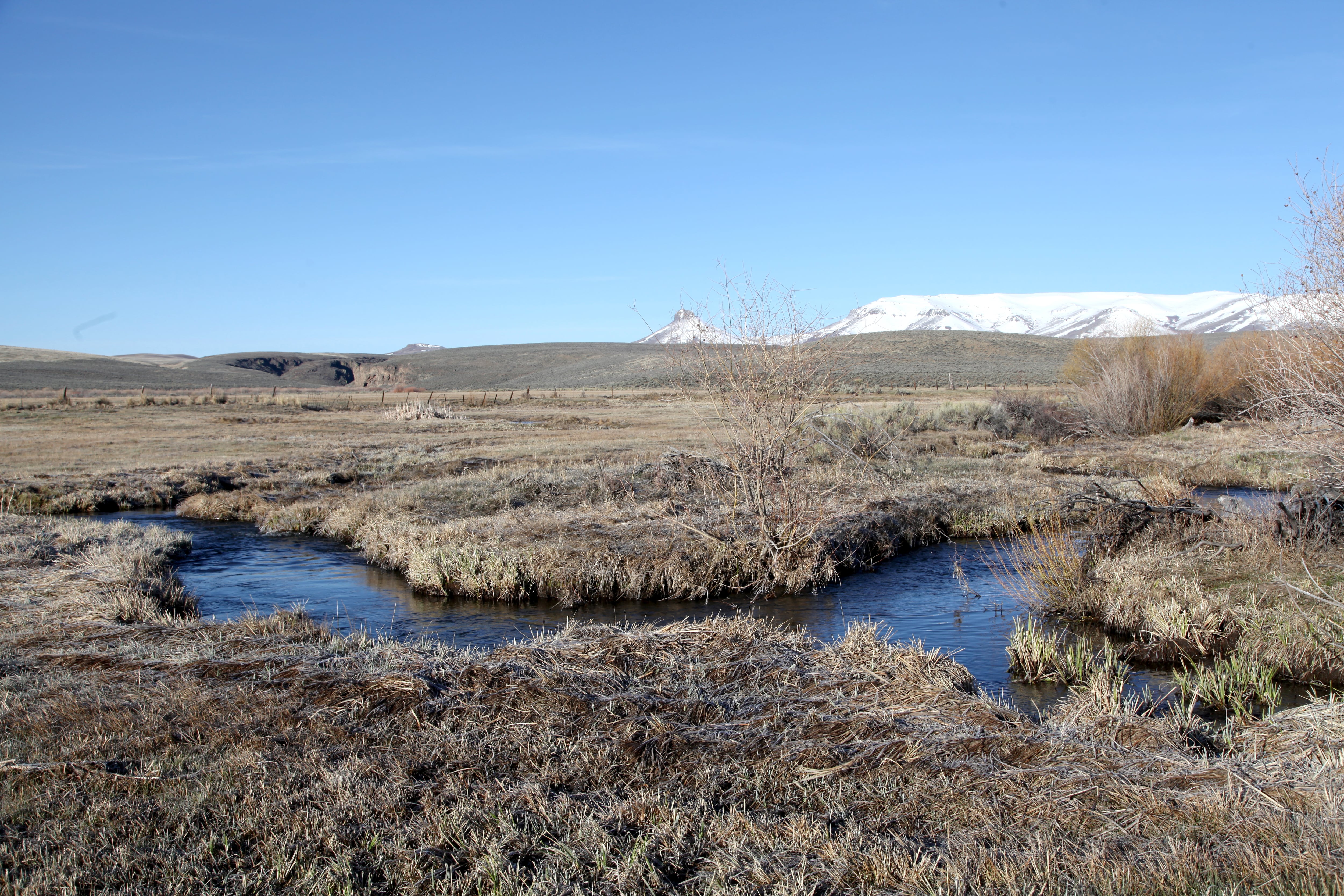

Biologist Jack Hansen started up an ATV and drove through a dark sea of sagebrush just before dawn on a snowy morning in early April.

This is what he does every spring morning to monitor about a dozen sage grouse mating sites scattered across more than 250,000 acres of Roaring Springs Ranch near Frenchglen in southeast Oregon.

As a low, gray light slowly filled the sky, he stopped the rig.

“The blinds are out there about 200 yards,” he whispered. “So we’ll walk out there, get our chairs set up, and hope we can see some birds.”

Hansen works as a full-time wildlife biologist for the ranch, an unusual job that grew out of an unprecedented agreement to protect the greater sage grouse.

Monitoring sage grouse mating sites is one of many ways Roaring Springs Ranch works to help these birds in exchange for the promise of legal protection should they ever be listed under the Endangered Species Act.

Over the last 10 years, nearly 1,500 private landowners across 11 Western states have been working to minimize their impacts on sage grouse and improve the birds’ habitat.

So far, they’ve managed to avoid an endangered species listing. But now, in the heart of a sage grouse stronghold in southeast Oregon, there’s a new threat looming from mining companies that want to drill for lithium, a valuable metal in batteries for electric vehicles and renewable energy storage.

On Monday, a mining company got federal approval to do exploratory drilling for lithium on federal land southeast of Roaring Springs Ranch. The work could eventually lead to a lithium mine in some of the best remaining sage grouse habitat in southeast Oregon.

As the Trump administration pushes for U.S. energy dominance, similar threats to sage grouse habitat are multiplying on federal land across the West and could upset the delicate balance ranchers have worked hard to strike with their sage grouse neighbors.

Hansen’s job as a ranch biologist is part of that balance. Through a scope on that chilly April morning, he spotted about two dozen ground-dwelling sage grouse at a mating site — known as a lek — and added them to his ongoing population count, which he shares with Oregon wildlife officials.

The male sage grouse look like small turkeys with big chests and pointy tail feathers that fan out behind them. During mating season in spring, they do what they’re famous for: To attract females, they puff out a pair of yellow air sacs on their chest and make a distinctive popping sound.

“Basically, they strut for the females,” Hansen said. “They show off.”

About a decade ago, the rapid decline of these birds across the West threatened to make them the spotted owl of the high desert — an imperiled and politicized species at the center of contentious fights over public lands.

“They were potentially going to get listed on the endangered species list because of how poorly the populations were looking around the West,” Hansen said.

Then, in 2015, ranchers, environmentalists and government agencies agreed to work together to keep these birds off the endangered species list.

A decade of voluntary conservation

Sage grouse once roamed 13 states in the West, feeding off sagebrush leaves and dancing their elaborate courtship strut, but they now only occupy about half of their historic range.

Roaring Springs Ranch Manager Stacey Davies was one of many ranchers in southeast Oregon who signed conservation agreements to protect sage grouse on private land in the hopes of keeping the struggling species off the endangered list.

“I would much rather focus on money going to healthy environments than regulation,” Davies said. “A species that is listed makes life miserable, honestly.”

An endangered species listing for sage grouse would add new restrictions on where ranchers can graze their cows and could even put them out of business.

But by 2015, sage grouse populations clearly needed help. Their numbers had declined by about 80% since the 1960s as development claimed more and more of their habitat across the West. The coordinated plan to recover the species without Endangered Species Act protections was deemed the largest landscape-level conservation effort in U.S. history.

The conservation agreement for Roaring Springs Ranch required the ranch to monitor sage grouse and improve the birds’ habitat, and to make sure that work was done right, Davies said, the ranch hired a professional biologist.

Among the many actions the ranch has taken to help sage grouse are adding reflectors to its barbed wire fencing to prevent sage grouse from flying into them, building water reservoirs that are fenced off from cows and cutting down juniper trees that give sage grouse predators a place to perch and compete with the native plants sage grouse depend on.

The ranch has also fought to control invasive cheatgrass that is known for fueling wildfires — one of the biggest threats to sage grouse habitat.

All of this work appears to be paying off for the sage grouse on the ranch. Hansen said he documented a 13% increase in the population two years ago and a 4% increase last year.

According to Davies, the cows and the ranching business are doing well, too.

“As we managed for ecosystem health, things that were good for fish are good for sage grouse are good for songbirds, good for mule deer, but they’re also good for the economics of the ranch,” Davies said. “We actually became more profitable while benefiting the environment. It just took change, and it took the willingness to look at it differently.”

According to Skyler Vold, sage grouse coordinator for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, while other ranches across southeast Oregon might not have hired their own wildlife biologists, they have taken similar actions to boost sage grouse numbers. And many of those actions also improve rangeland health for cattle.

“Really, what’s good for the herd is generally good for the birds,” Vold said.

Vold helped document a 63% increase in Oregon’s sage grouse populations last year, though he noted the state’s population is still down 33% from what it was historically.

Mining threat highlights environmental trade-offs

Sage grouse evolved in a vast sagebrush sea, Vold said, and they need big, uninterrupted landscapes to thrive. Anything that breaks up their habitat can threaten the bird’s survival, whether that’s wildfire, renewable energy development or mining operations.

"So we’re pretty concerned about that down in the McDermitt Caldera," Vold said.

For years, Australia-based mining company Jindalee Resources Ltd. has been exploring the idea of developing a lithium mine in the McDermitt Caldera in southeast Oregon near the Nevada state line.

The caldera is an ancient supervolcano that hosts one of the largest known lithium deposits in the U.S. Lithium Americas has already started developing the Thacker Pass lithium mine on the southern end of the caldera in Nevada.

This week, the Bureau of Land Management approved a permit for the company’s subsidiary HiTech Minerals Inc. to do exploratory drilling for lithium across 7,200 acres of federal land. It’s the first step toward developing a full-scale mine on the Oregon side of the caldera.

Lithium plays a key role in the current push to move away from fossil fuels that contribute to climate change. It’s used in batteries for electric vehicles and renewable energy storage. But extracting it from the earth is disruptive to existing ecosystems, creating a kind of environmental paradox.

Vold said the problem he sees with Jindalee’s proposal is that the project area is also a verified sage grouse hotspot with no existing development around it. In its record of decision, the BLM noted that there are four occupied sage grouse mating leks within Jindalee’s exploratory drilling project area and another 25 leks within 3 miles.

“It’s just a really intact sagebrush sea,” Vold said, “and if a giant open pit mine were to go in here, it would not be good for these populations of sage grouse, let alone any other species in the caldera.”

In its environmental review, the BLM found the project will result in “temporary loss of habitat” and “fragmentation” for sage grouse and that the noise, human activity and vehicle traffic may displace wildlife in the project area.

But the agency concluded that working in phases, restricting driving speeds and a seasonal shutdown from December through June will limit the impacts to the birds.

The BLM received approximately 2,300 public comments on the exploratory drilling proposal that have not been released to the public, public affairs officer Jeanne Panfely said in an email.

‘We’ve been protecting that caldera’

Over the past 30 years, fourth-generation rancher Nick Wilkinson has rearranged his entire ranching operation to protect threatened Lahontan cutthroat trout and declining sage grouse. Keeping the cows from damaging their habitat meant cutting his herd in half and leasing more grazing land near his ranch, which straddles the Oregon-Nevada state line.

“If somebody five years ago would have come to me and said, ‘I’ll bet you a million dollars they open up a lithium mine in the caldera,’ I’d have bet on my ranch they wouldn’t because of the stuff that I’ve been through with the fish and the sage grouse.”

Now, to protect wildlife habitat while keeping his cows fed, Wilkinson needs to move his cows around quite a bit. And in the springtime, he said, the federal land where Jindalee wants to explore for lithium is the only place he has to graze his cattle.

The mining company is now cleared to build about 22 miles of roads and drill up to 168 holes in the land he leases from the Bureau of Land Management.

Wilkinson says that an exploratory drilling operation alone could put his ranch out of business. He had hoped to pass it on to his son and grandson, who represent the fifth and sixth generations of his family’s ranch.

“If that project goes in, I just don’t see how we can coexist,” he said. “It’s the only place we can turn these cattle loose this time of year.”

Jindalee’s mining claim is one of many surrounding Wilkinson’s ranch, and the family has seen the damage left by old mines that still pollute the landscape. But Wilkinson said he knows the government land he’s leasing is fair game for mining operations.

“I realize we need clean energy,” he said. “I’m not going to argue. … It’s government ground. It belongs to the public. But I want there to be some mitigation. If you want to take away my operation and my grazing, then buy my ranch.”

Jindalee CEO Ian Rodger said his company’s project is still in the early exploratory stages at this point and won’t put any ranches out of business. A lithium mine is still a long way off and would require a lot more permitting.

“Ultimately, if we’re successful, you know, that’s the way we would look to go,” he said. “But at the moment we’re actually only looking to do exploration to basically prove up our future plans.”

He said the lithium deposit in the McDermitt is globally significant.

“It’s recognized by industry professionals,” he said. “Its scale is immense.”

And the modern world increasingly needs this metal for all kinds of batteries, he noted, including everyone’s personal electronic devices, electricity storage for the grid, artificial intelligence and military drones.

“The average soldier has 20 pounds of lithium-ion batteries,” he said. “It’s a very important critical element.”

The large lithium deposits in the McDermitt Caldera can provide “meaningful supply over generations,” he said.

Rodger said the company is doing preliminary work to design its project “to have the smallest footprint possible” and has committed to avoiding critical sage grouse habitat — especially during mating season.

But Wilkinson still sees a threat both to his ranch and to the sage grouse he’s been trying to help.

“We’ve been protecting that caldera … we’re just going to destroy it?” he said. “If you let this happen, don’t you dare ever open your mouth about listing that bird.”

News Source : https://www.opb.org/article/2025/12/12/oregon-sage-grouse-lithium-mine-nevada/

Other Related News

12/12/2025

The photos were released without captions or context and include a black-and-white image o...

12/12/2025

HURON SD American farmers are welcoming the 12 billion assistance package President Trump...

12/12/2025

MOUNT VERNON Wash AP Days of torrential rain in Washington state caused historic floods t...

12/12/2025

Subscribe to OPBs First Look to receive Northwest news in your inbox six days a weekGood m...

12/12/2025