Published on: 08/06/2025

This news was posted by Oregon Today News

Description

Editor’s note: This is the second in an occasional series about how East Portland neighborhoods are experiencing district representation in the city’s new government. Find our previous reporting here.

If you asked where downtown Portland was on a map in the early 1980s, a young Steph Routh would have pointed to Gateway Shopping Center.

“For me, it was the city center,” said Routh, now 49, who grew up walking distance away from the commerce hub at Northeast Halsey Street and 102nd Avenue. Routh remembers running into friends in the parking lot and the bustling mom-and-pop storefronts. “It was just full of treasures — a bead shop, a music store. It was where you wanted to be.”

That was the vision that Gateway’s architects had in mind.

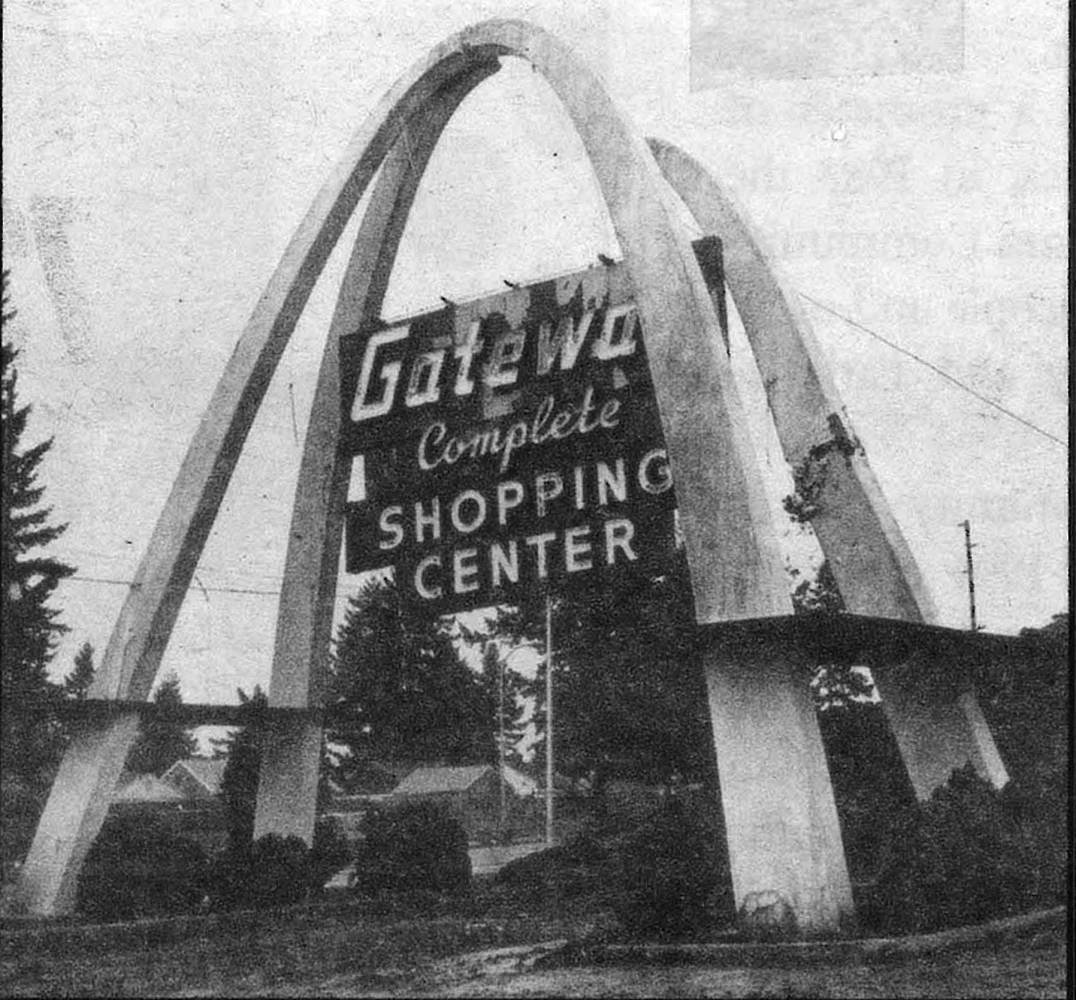

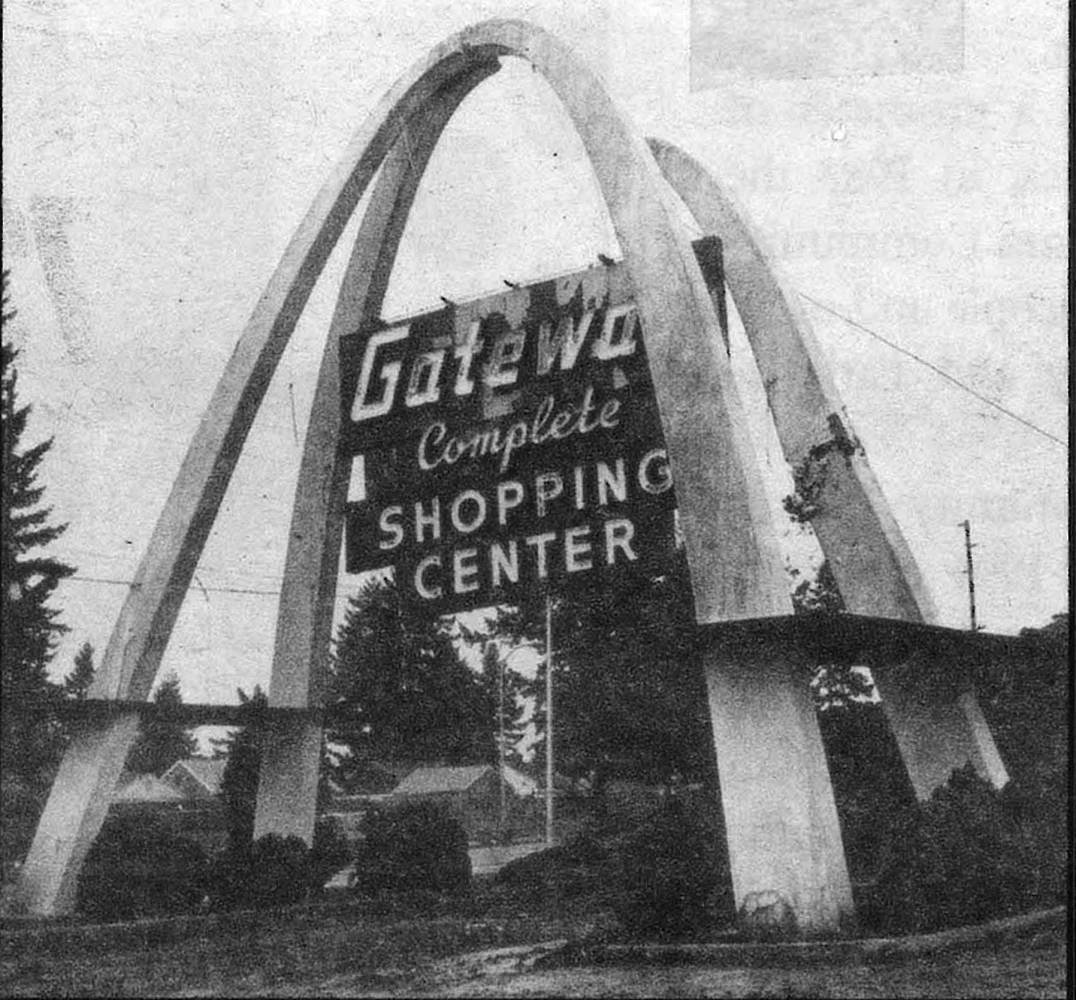

When grocery store owner Fred Meyer opened the suburban shopping center in 1954, he envisioned a “gateway” to economic development and community growth seven miles east of downtown Portland — complete with a large concrete arch in the parking lot. It worked, attracting new residential development, businesses and, eventually, an active public transit center.

But that dream is now a thing of the past.

Despite a decades-old city plan to cement the shopping district as Portland’s “second downtown,” years of economic upheaval, land use challenges and perceived political indifference have left Gateway a shell of its past self. Vacant buildings and abandoned parking lots have become a backdrop for the city’s sprawling homelessness crisis and violent crime.

In June, a “For Sale” sign appeared on the roughly 25-acre shopping center. Last month, the Fred Meyer store that had anchored the property for more than 70 years announced it will close its doors in September.

For many, the shopping center’s demise is a symbol of decades of city leaders’ disinvestment in the economic health of East Portland and its largely low-income residents. Others see an opportunity. Portland’s recent government overhaul assigned dedicated council members to represent East Portland for the first time in history. Gateway’s downturn could be a chance for the city to show what true political representation in East Portland could mean.

“Fred Meyer closing, it’s the latest data point telling us that we don’t matter out here,” said Routh, who still lives in East Portland, and now chairs the city’s planning commission. “It’s hard news. But it doesn’t have to be the end of our story.”

A HISTORY OF DISTRUST

The history of the Gateway district is marked with distrust.

When Meyer, by then a household name in Portland for decades, built his shopping center in the 1950s, the property was in unincorporated Multnomah County. Building outside of city limits offered fewer regulatory hurdles and taxes, a selling point for both businesses and homeowners alike.

Portland annexed most of these neighborhoods in the 1980s, promising improved roads and utilities. Longtime residents still talk about the shock of the first massive sewer bill they received after the switch. Frieda Christopher has owned her home in what is now East Portland’s Hazelwood neighborhood since the 1970s.

“A lot of promises were made,” said Christopher, 75. “Paying for sewer upgrades, that was part of the deal. But they were also supposed to improve streets and sidewalks and parks, which they never did.”

This resentment only grew. In 2000, the city adopted a sweeping redevelopment plan to invest in transportation, housing and public spaces in the 658-acre Gateway district. In doing so, the city turned Gateway into an urban renewal district, a process that allowed the city to borrow money to make public improvements in the district over 20 years, then use the increase in property taxes over that time period to repay debt. In all, the city was able to borrow $164 million with inflation over that time period.

It was one of the first of these districts — now called “tax increment financing” or TIF districts — on Portland’s outer east side, following projects in the Lloyd District and along Interstate Avenue in Northeast Portland. Located at the convergence of two major freeways, multiple light rail lines and several bus lines, the district felt primed to become a lively commerce hub.

“The Gateway district, projected to be the most accessible location in the Portland metro region in 20 years, is envisioned by many to become a new center for the people of east Portland,” reads the city’s redevelopment plan.

Brian Moore is the development manager at Prosper Portland, the city urban development agency that oversees these districts.

“The Gateway TIF district was an effort to support the expansion of the transit system, and focused on trying to catalyze transit-oriented development,” Moore said. “That was the need.”

Neighbors were largely optimistic about this goal. But an early political deal with Multnomah County forced a large chunk of the initial TIF money to be given to the county to run a shelter for child abuse victims, sowing distrust in what had been pitched as a fair process. Other investments were slow to come. Christopher, who sat on the volunteer committee that shaped the 2000 Gateway redevelopment plan, said she felt city leaders were distracted.

“This was the same time that the Pearl District was taking off and getting a bunch of attention,” she said, referencing the Northwest Portland urban renewal district that won national acclaim for its strategic transformation. “It was obvious that’s where the city wanted to focus its attention. Not us.”

DEVELOPMENT HURDLES

The urban renewal money did result in some notable developments, like extending the Green Line MAX line to Clackamas County, building a parking garage near the transit center, and helping finance affordable housing projects. According to Prosper Portland, the city added roughly 700 new housing units to the Gateway district since 2010.

The most popular development is the $8 million Gateway Discovery Park on Northeast Halsey Street, which opened in 2023 and features a skatepark, picnic tables and a playground accessible to kids with disabilities. The park is adjacent to another admired renewal project, the $32 million Nick Fish building, which opened in 2021 and contains both low-income apartments and office space.

Through the urban renewal plan, the city has also helped buy land, identify tax credits and find other incentives to attract private sector development in Gateway. That has attracted businesses like the Oregon Clinic, Portland Adventist Community Services, and the Portland Garment Factory.

But in the last decade, most outside investment in Gateway has ground to a halt.

Nidal Kahl has owned a furniture store on Northeast Halsey Street for 25 years, during which time he joined and led the Gateway Area Business Association. While the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic — months-long store closures and a shift to online shopping — devastated his business, Kahl said that onerous city regulations have been largely responsible for the district’s economic stagnation.

“It’s the bureaucracy,” he said. “You’re not going to have people developing if the barriers to development continue to grow.”

In 2016, Kahl sought to build a second floor on his business. He hoped to lease the space out to other local organizations.

Kahl went to Prosper Portland, which helped pay for a feasibility study — one way the agency tries to lower costs to spur new construction. Kahl said he learned that, if one of the building’s original beams crumbled during construction, city regulations would require the entire building to be leveled.

“If that were to happen, it would force me into bankruptcy,” he said. “So what am I going to do? All I wanted to do was make an investment in my community. But I couldn’t.”

The city has made other financial barriers to development in Gateway. One is the fact that new developers are required to pay for the infrastructure that the city never completed when it annexed these neighborhoods.

“Pretty much all private development on large properties requires millions of dollars investment in sidewalks, roads, and other infrastructure that doesn’t exist,” said Brian Moore, development manager at Prosper Portland.

This has made it hard to lure new developers who don’t have to pay for these infrastructure costs when building in other areas of Portland.

And unlike new builds in wealthier parts of town, developers can’t set rents too high. But, because construction and labor costs remain the same across the city, Moore said the payoff is low.

“It’s a hard sell,” Moore said.

BAD FOR BUSINESS

Once development comes to Gateway, keeping it there is another challenge.

Fred Meyer gave little reason for its closure in July. Spokesperson Tiffany Sanders said the decision was “part of a larger company-wide decision to run more efficiently and ensure the long-term health of our business.”

A month earlier, Fred Meyer owner Kroger announced it would be closing 60 stores nationwide in an attempt to improve profits.

Locally, Fred Meyer has publicly spoken about problems with shoplifting in the past, an issue that inspired stores to partner with Portland police to provide security and check customers’ receipts in recent years.

Councilor Jamie Dunphy, one of three councilors who represent East Portland’s District 1, said the city’s inability to address its homeless crisis — paired with sparse police resources — have converged to make Gateway a hard place to attract business or customers.

“We built some of the best public transportation infrastructure in Gateway, but our failure to respond to homelessness has turned the MAX into a day shelter,” said Dunphy, who lives in the nearby Parkrose Neighborhood. “And now, the transit center feels genuinely unsafe at times.”

The Gateway Shopping Center is located in the Hazelwood neighborhood, which has the highest crime rates of any neighborhood east of the Willamette River, according to Portland Police Bureau records. Other businesses point to theft and safety concerns as an impediment to business. Saysana Jeung managed Lily Market for 20 years. The family-owned Asian grocery store lies three blocks east of the shopping center on Northeast Halsey Street, nestling among other businesses. It was busy on a recent Friday afternoon, and Jeung deftly dashed between answering the phone, assisting customers and restocking shelves.

“It’s really sad to see Fred Meyer go,” Jeung said. “But I don’t blame them.”

Jeung said his business has seen an increase in theft in recent years, paired with the increase in homeless campers on the adjacent sidewalks and parking lot. He said that this has made it hard to attract customers and has made staff feel unsafe when they’re leaving work at night.

Mayor Keith Wilson’s office has partnered with bigger businesses, like Fred Meyer and the Oregon Clinic, to provide security or expedite homeless camp removals.

Jeung said he didn’t get the same kind of response when he reached out to the city.

“I know they are trying,” he said. “But it feels like us small businesses in East Portland aren’t getting the same kind of attention.”

COMMUNITY IMPACT

While there are other grocery stores in the area, Fred Meyer’s closure means the loss of a pharmacy, basic home goods and clothing store.

Carla Ricardo, a longtime Fred Meyer customer, clutched her chest when talking about the pending closure.

“It’s going to hurt,” said Ricardo, talking to OPB outside the grocery store last Friday. “It’s the only pharmacy in the area. I’m lucky I have a car, but not everyone who relies on this store can just drive over to CVS.”

The store’s closure also means the loss of some 250 jobs. While Fred Meyer has promised to relocate its Gateway staff to other stores, it remains a net job loss for East Portland.

Out of the four council districts, District 1 is home to the most families, people of color, and people below the federal poverty line, which is an annual income of $32,150 for a household of four. These are Portlanders who need access to the kind of entry-level jobs Fred Meyer offers, according to longtime East Portland resident Terrance Hayes.

“East Portland is a working-class community,” said Hayes, who owns a graffiti removal business and unsuccessfully ran to represent East Portland’s District 1 on the city council last year. “Jobs like Fred Meyer, this is how people pay their bills, how young people are trained for the workforce, how elderly people can make ends meet.”

Hayes said if people in East Portland have to commute across town for work, where they may shop or buy a meal after work, that could also hurt the district’s economy.

“East Portland has to find a way to be economically vibrant,” he said, “and that has to start with people from East Portland that get to work in East Portland and get to spend money in East Portland.”

A NEW OPPORTUNITY

Before this year, only two Portland city councilors had ever lived in East Portland. The old city council members were elected citywide, not by geographic districts, and candidates and campaign donors tended to come from wealthy neighborhoods closer to downtown. Many longtime neighbors believe this is one of the reasons why their community’s issues have been ignored in City Hall.

That imbalance was addressed last November when East Portland voters in the brand-new District 1 elected three councilors who live in their district to represent them.

“Previously, we have suffered from a lack of political will,” said Routh, the planning commission chair who also unsuccessfully ran for a District 1 council seat last year. “But now, I think, we have an opportunity for unprecedented political will. That is an ingredient we have not had before.”

Routh wants to see the district’s new leaders create a plan to purchase or redevelop the Gateway Shopping Center, tapping into the remaining funds in the Gateway TIF coffers.

The Gateway TIF didn’t expire in 2022 as anticipated. Instead, the city council voted to allow the city to continue borrowing money for public investment in the area for five more years. That unlocked about $60 million.

As of July, much of that money is already earmarked for projects, including a $10 million project to build a new 250-unit housing development across the street from the Gateway retail center.

Meanwhile, real estate company CBRE is asking $50 million for the shopping center.

Moore with Prosper Portland said there’s flexibility for the other funds to be used on new projects in Gateway. But the city will need input from the community and current property owner before moving forward with any plan.

“This is a complicated site, and it’s a complicated real estate deal,” said Moore. “But we believe that we’re well-positioned to help be a partner in that process.”

But, like in the past, Portland may be distracted. Last year, the city council created six new TIF districts — three in District 1 alone — that will require Prosper Portland staff and time to get off the ground. That could leave few resources to focus on helping Gateway.

“Another chance to ignore us,” said Christopher.

She wants to see the city treat Gateway Shopping Center like they have other big public-private projects, like the work to bring a major league baseball stadium to the South Waterfront or to open the James Beard Market downtown.

“East Portland has 25% of your population, it has most of your families,” said Christopher. “There’s potential here for something big.”

Mayor Wilson has begun meeting with Prosper Portland and private sector leaders about ways the city could leverage remaining Gateway TIF dollars to attract new development. In an email to OPB, Wilson said the situation presents the city with a “unique opportunity.”

“The Gateway Regional Center is a large area with unrealized potential and excellent transit access,” wrote Wilson. “We are committed to fostering a vibrant, mixed-use neighborhood that includes commercial services and a variety of housing options for all income levels.”

Distinct 1 councilors also see an opportunity.

In City Hall, Councilor Candace Avalos is consistent in her advocacy for more housing. But when thinking about East Portland’s needs, she’s thinking bigger.

“We have a need for more housing and homeless services in East Portland, for sure,” she said. “But how do we use this as an opportunity to talk about other things that make a community thrive? Like small businesses and community spaces and places where people can live full lives?”

Avalos said she’s planning to convene community town halls in District 1 to hear directly from residents about the shopping center’s future. She’s already heard some creative ideas — from installing a temporary ice rink in the lot over the winter, to reopening the Portland Children’s Museum, which closed in 2021.

Dunphy is focused on the status quo. He believes that a grocery store like Fred Meyer is what neighbors need most.

“I appreciate the creativity, the ideas,” he said. “But we’re talking about the basic survival needs of a community and providing for your family within a reasonable distance of your home.”

He said he’s interested in talking with Fred Meyer leadership to convince them to stay open a little longer, so the city has time to plan next steps. Dunphy also sees an opportunity to reevaluate the city’s urban renewal model.

“Gateway was promised walkable business districts, vibrant economics, good transportation infrastructure, bike infrastructure,” he said. “Look around, you can’t tell. TIF districts have demonstrated repeatedly that they aren’t successful at accomplishing the goals they set at the beginning.”

Dunphy can’t stop the new TIF districts from coming online, but he can propose changes to the system going forward.

“I am going to make sure that I am there to push this process in the right direction,” he said.

In the meantime, councilors are looking for ways to bring more jobs to East Portland. In May, District 1 Councilor Loretta Smith spearheaded a policy that would use $200 million to fast-track sidewalk construction and maintenance in District 1 and District 4, in Southwest Portland.

“I expect it will create hundreds of jobs and apprenticeships in East Portland,” she said. “And it’ll help fix the infrastructure programs we inherited from annexation.”

ANOTHER CLOSURE

Inaction on Gateway brings its own risks.

Kahl, the furniture store owner, said he never thought he’d consider selling his business. Kahl immigrated to the United States from Syria with his family over 40 years ago. His family has left a considerable mark on Oregon — his father’s cousin was former Oregon Governor Vic Atiyeh, the first governor of Middle Eastern descent in the U.S.

When Kahl bought the store from his uncle in the 1980s, he saw an opportunity to continue his family’s legacy in Oregon by creating jobs and expanding the economy of East Portland.

“And I’ve told myself that when the going gets tough, you need to be creative. You have to persevere,” Kahl said. “You do it out of respect for the journey our family took.”

But that mindset has begun to shift as Kahl has struggled to redevelop his property and seen local businesses that bring foot traffic to his shop continue to go under. As part of this shift, Kahl has stepped back from his leadership role at the local business association, which hasn’t met in months.

He said he will soon have no choice but to sell.

News Source : https://www.opb.org/article/2025/08/06/east-portland-business-gateway-oregon-shopping-center-city-council/

Other Related News

08/08/2025

In June Providence notified 134 employees in Oregon including some union members that thei...

08/08/2025

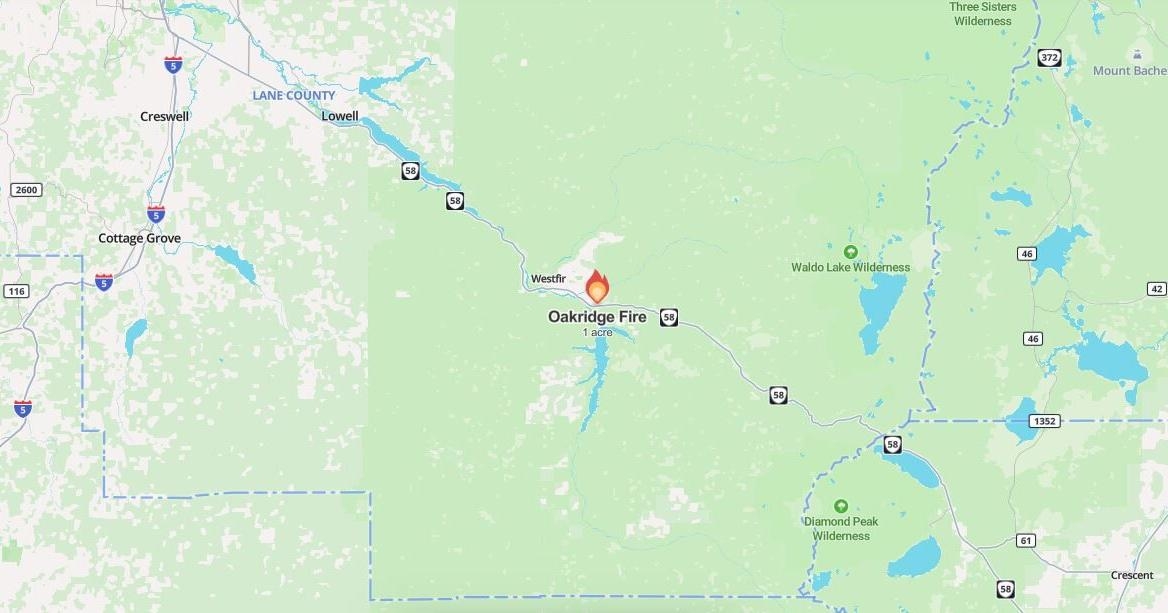

By KMTR and KTVZ News Staff OAKRIDGE Ore KMTRKTVZ Level 3 GO NOW evacuation orders were in...

08/08/2025

A Level 3 GO NOW evacuation is in place for Dunning Road residents in the Oakridge area du...

08/07/2025

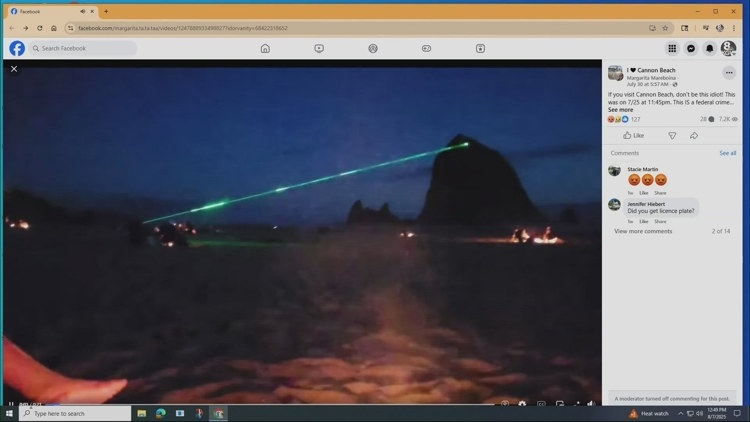

Video of laser harassment at Haystack Rock has prompted calls for wildlife protection afte...

08/07/2025