Published on: 06/01/2025

This news was posted by Oregon Today News

Description

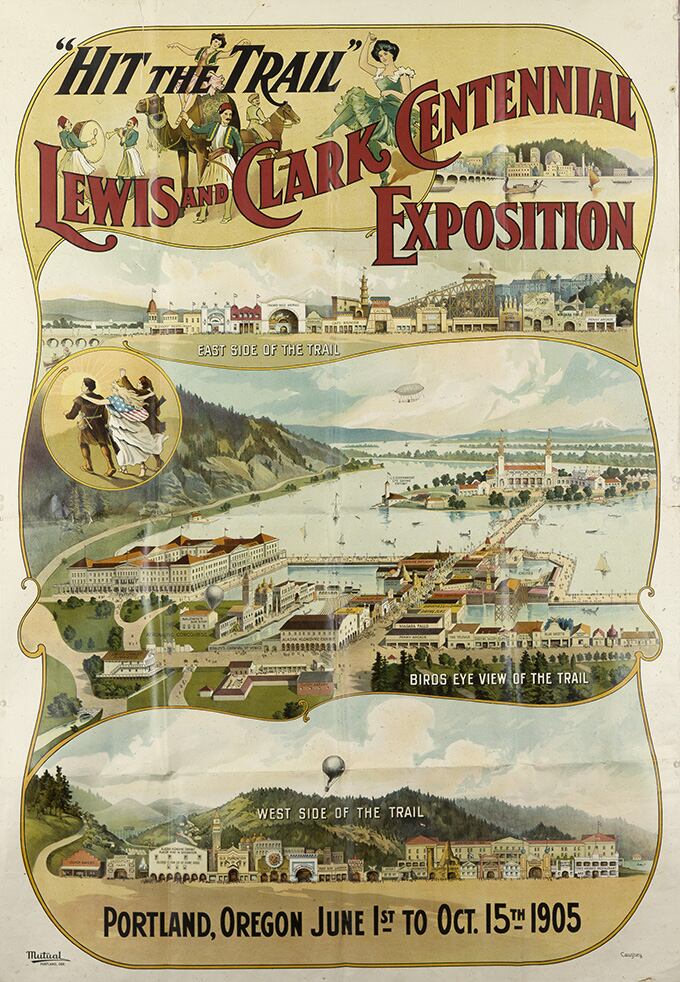

On June 1, 1905, nearly 40,000 people turned out for the opening day of Portland’s only “World’s Fair.”

Though it took place 120 years ago, photographs and memorabilia from the Lewis and Clark Exposition still fascinate, with images showing a temporary city of ornate buildings and thoroughfares surrounding a lake.

Today, it is all long gone.

Over the summer and fall of 1905, Portland hosted the Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition and Oriental Fair — more commonly known as the Lewis and Clark Exposition.

The event commemorated the 100th anniversary of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, but, really, it was a way for city boasters to introduce Portland to the nation.

At the time, Portland was competing with Seattle and San Francisco for regional influence and national recognition as an important industrial hub on the West Coast.

Although often called a “World’s Fair,” it was not officially recognized as one. It didn’t meet the strict international standards required for that designation.

Still, it was a major event for the city.

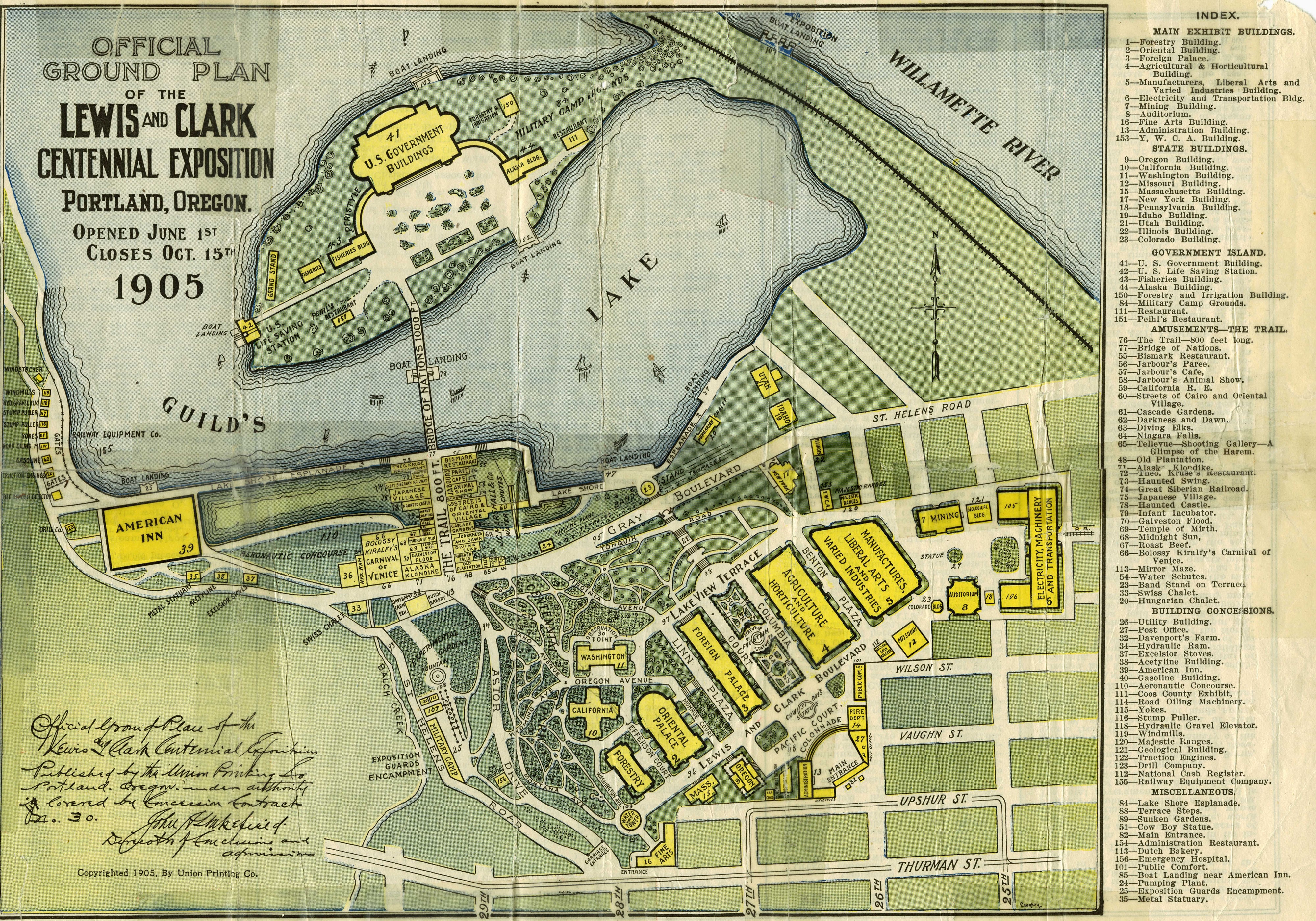

The 400-acre Expo fairground sat about two miles from downtown, and streetcars and ferries shuttled visitors back and forth, day and night.

Over four and a half months, the Expo drew more than 1.5 million visitors.

An estimated $8 million flowed into Portland’s hotels, restaurants, shops and other attractions — including the newly inaugurated Oaks Amusement Park. The Oaks opened just two days earlier and remains one of the nation’s oldest trolley parks.

Transforming Guild’s Lake

Today, the old Expo grounds are part of an industrial district in Northwest Portland, but in 1900, the area consisted of mostly muddy swamplands around Guild’s Lake.

Over the course of two years, developers built up the slough, creating landscaped terraces with wide promenades and decorated buildings that circled an artificial lake.

When crowds arrived on that first opening Thursday in June, they experienced a miniature, international city with buildings modeled in Spanish Renaissance style. Domes, arches and cupolas were lit up with bulbs, creating a mesmerizing scene for those unused to seeing so much electricity on display.

It must have been quite a sight for Portlanders and its many visitors.

Images on the Oregon Historical Society’s Digital Collections website and the Multnomah County Library‘s online gallery give modern viewers a glimpse of what quickly came and went.

Those elaborate structures were built to be temporary. When the Fair closed, most of the buildings came down.

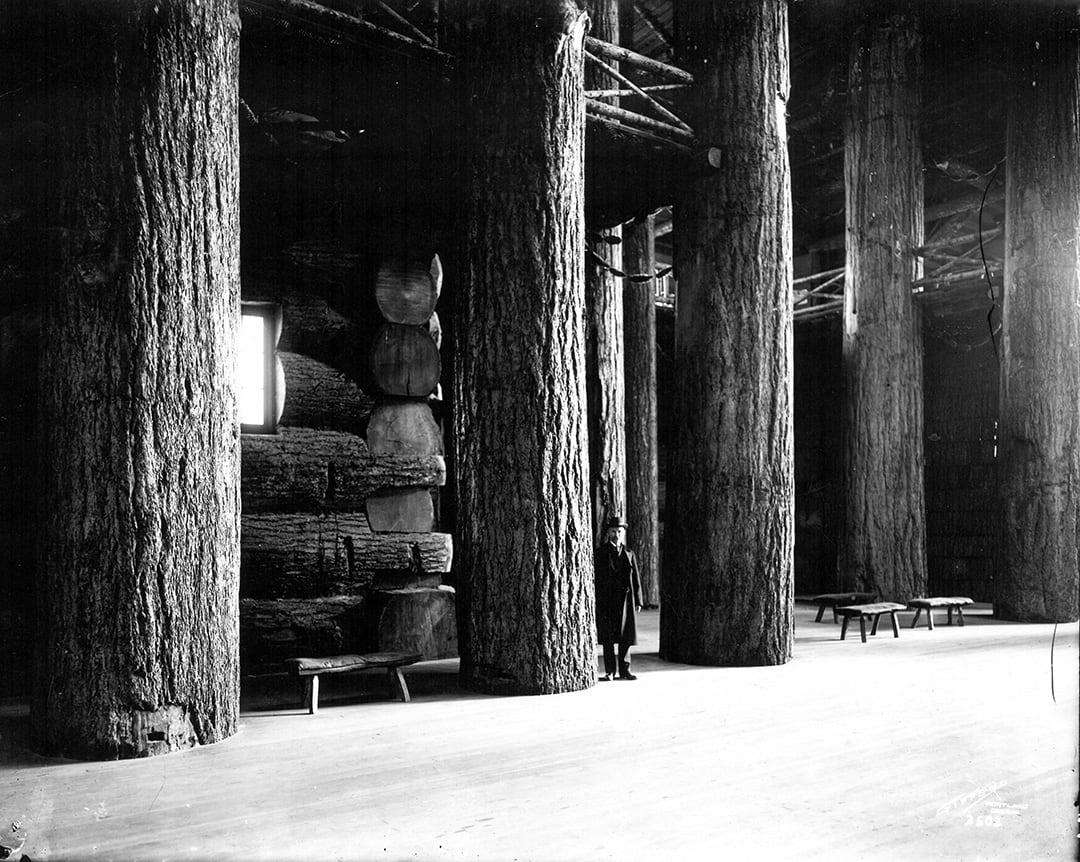

The one exception was the Forestry Building, known as the “log cathedral.”

The Log Cathedral

Made of massive Douglas firs stacked 72 feet high — about seven stories — the Forestry Building was sometimes called the largest log cabin in the world. That’s likely not true. The National Park Service’s website gives that distinction to Yellowstone’s Old Faithful Inn, which still stands.

Still, the building was impressive, covering nearly half a city block. According to Offbeat Oregon History, it required 1 million board feet of lumber, handpicked by timber baron and philanthropist Simon Benson, probably best remembered for the Benson Bubbler drinking fountains he donated to the city of Portland.

Inside the log structure, exhibits showcased the Northwest timber industry.

With the closing of the Fair, the city of Portland purchased the building but didn’t seem to know what to do with it. It remained neglected for several years. In 1964, an electrical fire left the building destroyed.

Soon after, civic leaders raised money to replace the structure, which still stands as the Western Forestry Center, located in Washington Park across from the Oregon Zoo.

Racism on display

The Fair’s motto, “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way,” reflected the expansionist thinking of the time, with exhibits celebrating the white settlement, growth and development of the Pacific Northwest.

A popular part of the Fair, known as “The Trail,” featured ethnographic exhibits that displayed people from colonized regions in stereotypical and often demeaning ways. For an extra fee, visitors could observe Native American, Filipino and Japanese people.

A 1905 article in The Oregonian reported, “The Hindoo fortune tellers, snake charmers and magicians are to be seen on the Trail at any time of day.” Performers wore costumes, lived in specially constructed quarters, and took part in staged ceremonies.

One report from The Oregonian stated, “They live at the Fair the same as they do at home. They wear the same costumes, all of which are grotesque and almost absurd to the average visitor ... and refuse to fight against becoming Americanized.”

These displays illustrated a narrative of Indigenous and colonized peoples moving toward “civilization.”

The official fair program stated, “This is the first exhibition ... where the general public have had the opportunity of examining the character of the training given people in the Government Indian schools.”

A lasting legacy

Throughout the course of the Expo, over 1.5 million visitors passed through the gates, many going more than once. The actual attendance was even higher. It is thought that over 400,000 visitors came from outside the Pacific Northwest.

The success of the Lewis and Clark Exposition encouraged Portland leaders to host the first official Rose Festival two years later, in 1907. Today, it remains a major annual event.

The Fair made a profit, a rare outcome for such events, and helped establish Portland as a destination for people seeking new opportunities.

The city’s population reflected this impact. In 1900, Portland had a population of just over 90,000 residents. By 1910, that number jumped to over 200,000.

Author’s note

When the Fair opened, volunteers from the Travelers Aid Society spread throughout the city and the Expo to offer newly arriving young women information about safe lodging and employment while also handing out food vouchers. The program was headed by Lola Baldwin. In 1908, the Portland Police Department hired Baldwin as the nation’s first female police officer. Baldwin was concerned that young women arriving in the city alone were vulnerable to crime and exploitation. Over the course of the Expo, the Aid Society assisted over 1,600 women and girls.

Baldwin’s concerns were justified. In 1893, a serial killer preying on visitors to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago murdered at least 27 women.

Several years ago, after reading the book “The Devil in White City” about those events, I did a deep dive into Portland’s 1905 missing persons and homicide cases. Despite tens of thousands of people arriving in the Rose City, my research didn’t turn up anything unusual for the time period. Baldwin and her crew of volunteers likely made a real difference in helping keep Fair visitors safe.

Related “Oregon Experience” Documentaries

News Source : https://www.opb.org/article/2025/06/01/oregon-experience-120th-anniversary-lewis-and-clark-exposition-portland-fair/

Other Related News

06/03/2025

The director of the Oregon Public Defense Commission announced on Monday a year-long plan ...

06/03/2025

PORTLAND Ore KOIN Thurston High School junior Brooklyn Anderson had one of the most excit...

06/03/2025

The Oregon Public Defense Commission has released a 12-month plan to reduce the number of ...

06/03/2025

BEND Ore KTVZ -- Tony Latrell Williams charged with stabbing 12 people on Sunday at a mens...

06/02/2025