Local News & Alerts

Heres a summary of everything that happened in Fridays Oregon OSAA high school boys and gi...

More

The US strikes on Irans Kharg Island targeted military sites but left its oil infrastructu...

More

When Brooke Cates arrived at West Linn as an assistant in 2017 she joined a girls basketba...

More

The states decision came after federal courts found that Drug Enforcement Administration a...

More

On Saturday at 140 am the National Weather Service issued an updated wind advisory valid b...

More

Media Release Case S2026-00378 Greenacres Ore- On March 12th 2026 at 515 pm Deputy H Fra...

More

On Saturday at 1249 am the National Weather Service released an updated winter weather adv...

More

The Trail Blazers push for a public commitment to transform the Moda Center into a state-o...

More

Dear Eric After more than a year together my boyfriend and I are planning to move in toget...

More

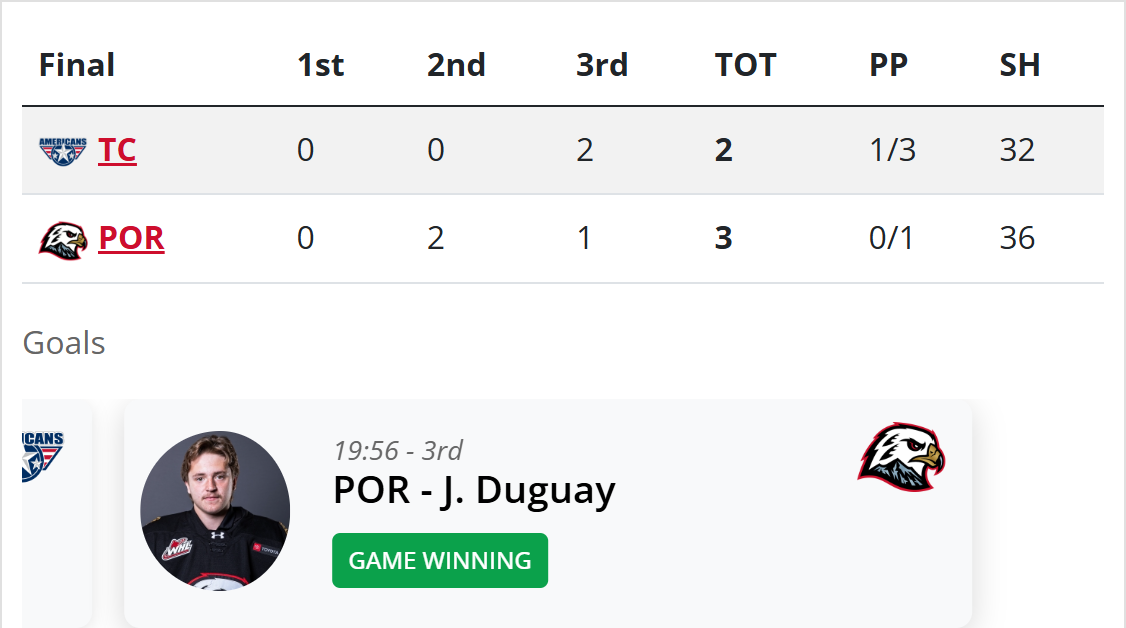

FOUND A WAYJordan Duguay scored his second of the game to secure the win pictwittercomZ1Op...

More

DEAR ABBY I just passed my 10th anniversary at the hospital where I am employed This occas...

More

McMINNVILLE West Albany coach Shawn Stinson calls his team a puzzle that fits together ni...

More

The illness is extremely rare On average two dozen adults are diagnosed each year in the U...

More

An alley-oop for the ages

More

A season-high four home runs powered No 18 Oregon State to a series-opening win over San D...

More

Vancouvers US Olympic gymnast Jordan Chiles is preparing for her final home meet with UCLA...

More

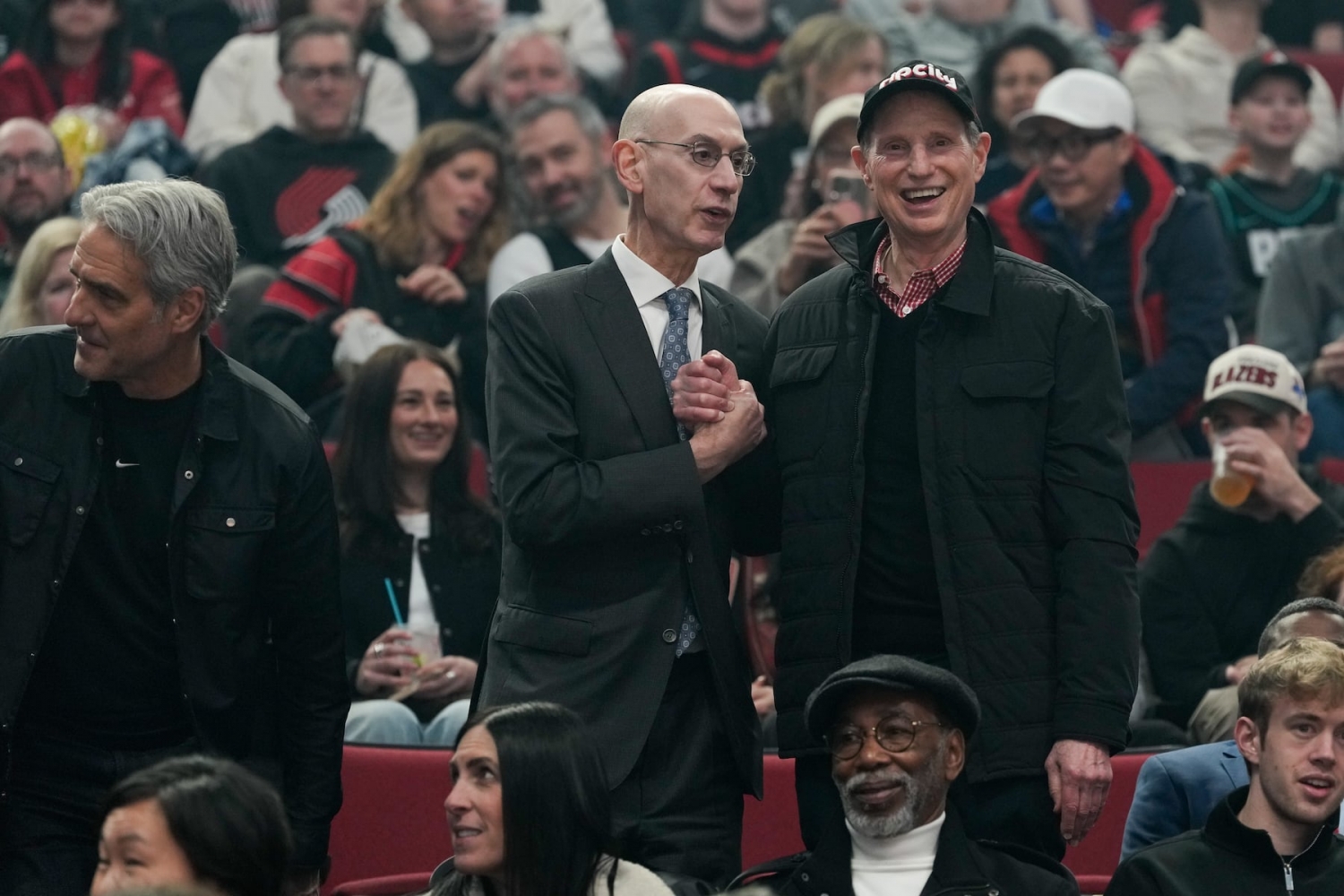

NBA Commissioner Adam Silver attended the Portland Trail Blazers game following the Oregon...

More

Anti-Muslim rhetoric is growing louder among some Republican lawmakers with Tennessee Rep ...

More

The US Embassy compound in Baghdad has been repeatedly targeted by rockets and drones fire...

More

Why should kids and teachers have all the spring break fun A central Oregon mountain town ...

More